Center

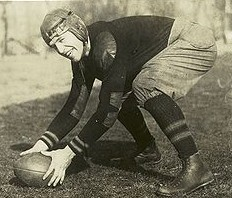

John McEwan (pictured) was Army's one consensus AA in 1914, and he is in the hall of fame. Quarterback

Vernon Prichard was a nonconsensus AA, and end Louis Merillat was a

consensus AA in 1913 and nonconsensus AA in 1914 (making 13 first-team

lists, yet not considered "consensus"!).

Center

John McEwan (pictured) was Army's one consensus AA in 1914, and he is in the hall of fame. Quarterback

Vernon Prichard was a nonconsensus AA, and end Louis Merillat was a

consensus AA in 1913 and nonconsensus AA in 1914 (making 13 first-team

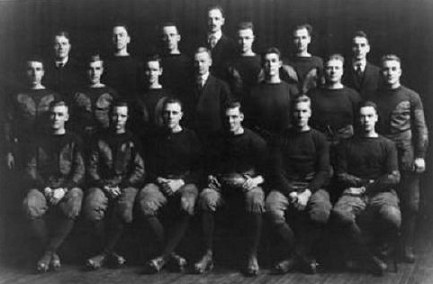

lists, yet not considered "consensus"!).In 1913, Army was down 6-0 to Colgate with 10 seconds left when Prichard ran off a 70 yard touchdown for a miracle 7-6 win. He and Merillat then became famous for the "Prichard to Merillat" passing plays that beat Navy at the end of 1913, though Army rarely passed otherwise. Navy had given up just 7 points prior to the Army game in 1913, and Army had not beaten them since 1905. Navy came into that game at 7-0-1, and 6 to 1 favorites to win, but Army beat them 22-9, Merillat scoring 3 touchdowns on 2 passes from Prichard and a 60 yard run. This season, the duo would strike down Navy again, Prichard throwing 2 touchdown passes, one to Merillat, and Merillat chipping in a blocked punt for a safety as well.

But the only starter besides McEwan to make the Hall of Fame as a player was tackle Alex "Babe" Weyand, despite the fact that he never made a first team AA list (that I have found), and was never mentioned as making a difference in a newspaper summary of a game (that I have found). Apparently it was "discovered" that Weyand had been a better player than Prichard and Merillat after he became well known for writing sports history books decades later.

Army's other end, Bob Neyland, had a stand-out game against Notre Dame and a great season from that point on. He is in the Hall of Fame as a coach, going 173-31-12 at Tennessee 1926-'34, '36-'40, and '46-'52. That record gives him a high ranking on the list for all-time coaching win percentage, just behind Harvard's Percy Haughton.

Lastly, halfback and punter Paul Hodgson deserves mention. He never made a first team AA list or hall of fame, but he was the bulk of Army's offense this season.

Presenting the greatest team

that even most college football history buffs have never heard of

Presenting the greatest team

that even most college football history buffs have never heard of