Much of Carlisle's success can be attributed to their Hall of

Fame head coach, Glenn "Pop" Warner. He coached at Carlisle 1899-1903

and 1907-1914, going 114-42-8. He is credited with inventing the

tackling dummy, screen pass, and shoulder and thigh pads, but his

greatest innovation was the single wing formation, which would dominate

college football offenses between the World Wars.

Much of Carlisle's success can be attributed to their Hall of

Fame head coach, Glenn "Pop" Warner. He coached at Carlisle 1899-1903

and 1907-1914, going 114-42-8. He is credited with inventing the

tackling dummy, screen pass, and shoulder and thigh pads, but his

greatest innovation was the single wing formation, which would dominate

college football offenses between the World Wars.Pop Warner's next stop after Carlisle would be Pittsburgh 1915-1923, where he went 60-12-4 and is credited with 3 national championships (I agree with 2 of these). After that, it was on to Stanford 1924-1932, where he went 71-17-8, coached in 3 Rose Bowls, and is credited with another national championship (I disagree).

Overall he finished 319-106-32 at 6 schools, setting a record for coaching wins that was later broken by Paul "Bear" Bryant and is now held by Joe Paterno.

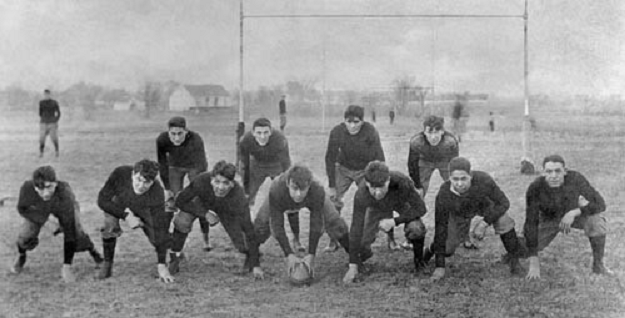

Halfback Jim

Thorpe is simply the greatest college football player of all time, and

with the modern shift to two platoon football and specialists, his

level of play can never again be approached. He was a tremendous ball

carrier, defensive back, placekicker, and punter-- during a time when

the kicking game was paramount (and thus great kickers were far more

prized and lionized than they are today).

Halfback Jim

Thorpe is simply the greatest college football player of all time, and

with the modern shift to two platoon football and specialists, his

level of play can never again be approached. He was a tremendous ball

carrier, defensive back, placekicker, and punter-- during a time when

the kicking game was paramount (and thus great kickers were far more

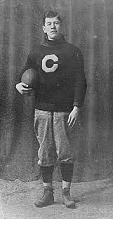

prized and lionized than they are today). Jim

Thorpe's best friend and roommate, quarterback

Gus Welch (pictured at left), is also in the College Football Hall of

Fame. He was Pop Warner's coach on the field, calling the plays, as he

was very smart-- an Honors student who later graduated from the

Dickinson School of Law.

Jim

Thorpe's best friend and roommate, quarterback

Gus Welch (pictured at left), is also in the College Football Hall of

Fame. He was Pop Warner's coach on the field, calling the plays, as he

was very smart-- an Honors student who later graduated from the

Dickinson School of Law.

I covered previous Princeton teams for my articles on the 1903 and

I covered previous Princeton teams for my articles on the 1903 and

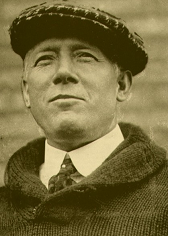

I've covered previous Minnesota teams for my 1903 and 1904

national championship articles, and I covered their Hall of Fame coach,

Henry Williams, in the 1903 piece. By 1911, Henry Williams (pictured at

left) had become one of the best known and most respected coaches in

football (he even had his own widely-published All American selections

this season). His "Minnesota shift" innovation (the now-standard

shifting of players during the count, then snapping right when they've

gotten into place) was sweeping across the country. In fact, after

years of rebuffing his offers to help them implement the shift,

Williams' alma mater Yale

had even adopted it (renamed the "Yale shift"). This was a

shocking development at the time, because the Old Eastern dogs simply

did not like learning new tricks from their Western pups.

I've covered previous Minnesota teams for my 1903 and 1904

national championship articles, and I covered their Hall of Fame coach,

Henry Williams, in the 1903 piece. By 1911, Henry Williams (pictured at

left) had become one of the best known and most respected coaches in

football (he even had his own widely-published All American selections

this season). His "Minnesota shift" innovation (the now-standard

shifting of players during the count, then snapping right when they've

gotten into place) was sweeping across the country. In fact, after

years of rebuffing his offers to help them implement the shift,

Williams' alma mater Yale

had even adopted it (renamed the "Yale shift"). This was a

shocking development at the time, because the Old Eastern dogs simply

did not like learning new tricks from their Western pups.