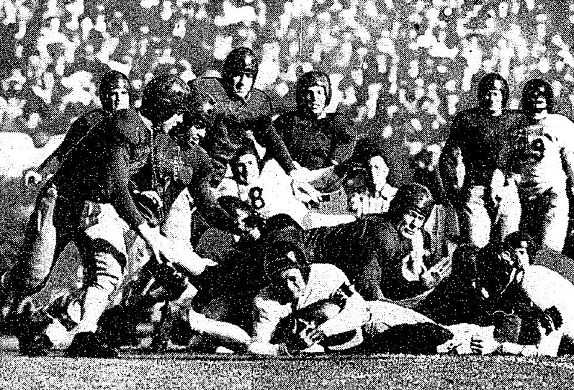

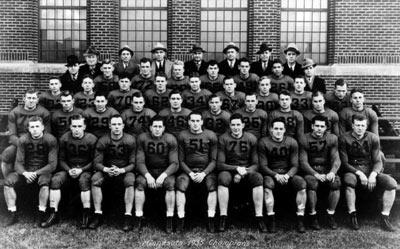

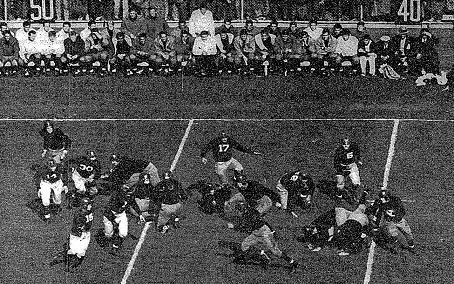

Defending their 1934 consensus national championship, Minnesota went 8-0 again this season, and they are again the unanimous choice for mythical national champion (MNC) among selectors listed

| North Dakota State (7-1-1) | 26-6 | |

| at Nebraska (6-2-1) | 12-7 | #24 |

| Tulane (6-4) | 20-0 | |

| Northwestern (4-3-1) | 21-13 | #18 |

| Purdue (4-4) | 29-7 | |

| at Iowa (4-2-2) | 13-6 | #22 |

| at Michigan (4-4) | 40-0 | |

| Wisconsin (1-7) | 33-7 |

This was Minnesota's 2nd straight 8-0 finish and consensus MNC. I covered their Hall of Fame coach, Bernie

Bierman, in my 1934 national championship article.

The 1934 team had been considered one of the best of all time, and

Michigan coach Harry Kipke had opined that their back-ups would beat almost

any team in the country. This season, they proved his assertion,

because nearly all their best players from 1934 were gone in 1935, and they

still went 8-0.

This was Minnesota's 2nd straight 8-0 finish and consensus MNC. I covered their Hall of Fame coach, Bernie

Bierman, in my 1934 national championship article.

The 1934 team had been considered one of the best of all time, and

Michigan coach Harry Kipke had opined that their back-ups would beat almost

any team in the country. This season, they proved his assertion,

because nearly all their best players from 1934 were gone in 1935, and they

still went 8-0.

| Penn (4-4) | 7-6 | |

| Williams (7-1) | 14-7 | (#26-32) |

| Rutgers (4-5) | 29-6 | |

| at Cornell (0-6-1) | 54-0 | |

| Navy (5-4) | 26-0 | |

| Harvard (3-5) | 35-0 | |

| Lehigh (5-4) | 27-0 | |

| Dartmouth (8-2) | 26-6 | (#26-32) |

| at Yale (6-3) | 38-7 |

| San Jose State (5-5-1) | 35-0 | |

| at San Francisco (5-3) | 10-0 | |

| UCLA (8-2) | 6-7 | #7 |

| at Washington (5-3) | 6-0 | #23 |

| Santa Clara (3-6) | 9-6 | |

| at Southern Cal (5-7) | 3-0 | |

| Montana (1-5-2) | 32-0 | |

| California (9-1) | 13-0 | #6 |

| Rose Bowl Southern Methodist (12-1) | 7-0 | #3 |

| Minnesota 8-0 | Princeton 9-0 | Stanford 8-1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1) Boand (math system) | 4.26 |

| 2) College Football Researchers Association | 4.22 |

| 3) Poling (math) | 4.11 |

| 4) Helms | 4.09 |

| 5) Sagarin-ELO (math) | 4.06 |

| 6) National Championship Foundation | 3.96 |

| 7) Dickinson (math) | 3.49 |

| 8) Houlgate (math) | 3.35 |

| 9) Billingsley (math) | 3.34 |

| 10) Sagarin (math) | 3.28 |

| 11) Parke Davis | 2.77 |

| 1) Houlgate (math system) | 4.5 |

| 2) Helms | 4.3 |

| 3) Parke Davis | 4.2 |

| 4) National Championship Foundation | 3.7 |

| 5) Billingsley (math) | 3.6 |